Notional Significance: Disinterment

[See all Notional Significance posts]

The entry to Bolton St cemetery is unremarkable: a gap in a white fence off a respectable street, a canopy of pines, plain crosses against a corrugated iron fence. But I know that I’m passing into a territory that would have the earth-magic wing of the psychogeographical movement panting with occult excitement. Iain Sinclair or Peter Ackroyd would have a field day with the plethora of obelisks, resonant names and eroded inscriptions, but wouldn’t that be the case with any cemetery? It’s like shooting mystical fish in a semiotic barrel. Nevertheless, certain monuments catch my attention, so I decide to play along.

There’s a broken marble column near the entrance, and at first I file this away as a symptom of vandalism or neglect, but a closer examination of the carving shows the break to be too clean. A shattered pillar seems like an obvious signifier (a life cut short; the futility and imperfection of human endeavour; all that Ozymandian sort of thing), but a little research unearths other connections. The Broken Column is an important symbol in Freemasonry, though perhaps a relatively recent one. What’s more, it seems that some Masons map the Three Great Pillars of Masonry to the Kabbalistic Sephiroth, and when the central column of Beauty is broken, it represents Man’s separation from divine knowledge: the severed pathway between Beauty and the Infinite. But in this place it was the act of building a pathway that caused a severance, tearing the cemetery in two when the motorway smashed its way through. Beauty and the Divine were certainly not on the Ministry of Works’ agenda.

As the path winds down into a severed gully, past other broken columns, I remember back to one of my first walks in Wellington, what seems like many decades ago. It was a gloomy, misty Sunday, with low cloud whipping through the treetops and fine rain drifting down through the dark foliage. The graves seemed shattered, lonely and abandoned, overgrown by indifferent vegetation, and my (shamefully Eurocentric) imagination turned this into a science fiction movie: a doomed colony on an alien world, the last remaining settlers burying their dwindling colleagues as the host planet erased their hubristic attempts at replicating home. Even today, in the brightness of late summer, the drooping aerial pohutukawa roots can seem monstrous, and by the time that I realise that they are also invaders here, I know it’s time to move on before my allegories tangle themselves into total incoherence.

But first, I come across a grave that even I can see is explicitly Masonic. The compass and set-square make that clear, even if I had to go back and look up the capital G (for God and Geometry, and perhaps for Gnosis), the stone ashlar, the tessellated pavement and the uneven columns topped with terrestrial and celestial globes. This lavish memorial to Captain Henry Tucker was erected by Captain Edwin Stafford, who later completed their pact by joining him in the grave. Such dedication would seem unusual today without a more intimate connection, and I wonder whether a different interpretation could be put upon the two upstanding columns than the Boaz and Jachin of Masonic lore. But it would be prurient and pointless to speculate about what the Herald called “the fine feelings, and the rare sentiment” between these two men. The pillars have been toppled in the past by falling trees and ‘60s yobbos (“because there’s nothing else to do in Wellington on a Sunday”), but they escaped the bulldozers. Their friendship can stand on its own terms.

Other monuments were not so lucky. Mass graves are not something one expects in New Zealand — they seem to belong to another world, a world of pogroms and plague pits — but the remains of 3,693 people are crammed into a “memorial vault” on the other side of the highway, their original tombstones scattered through the remainder of the cemetery. Time is a commodity that we can only value when it’s in our grasp: we’ll willingly mangle or erase the past to save a few seconds in the present, all the while burning through the resources of the future. Whole books could be written on the saga of the Foothill Motorway, but for the moment I’ll just mention that in 1965 a Councillor Morrison was reported as saying that “although some other transport system might be technically preferable the important consideration was that the National Roads Board had the money and was prepared to spend it.” Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

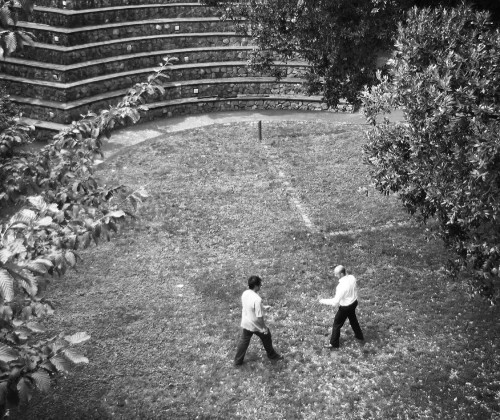

But the catastrophic changes wrought by the motorway construction were not the only reason why Margaret H. Alington called her history of the cemetery Unquiet Earth. From the start, this burial ground was fraught with contention, chaos and perturbation. Even before the land was granted, the plans were beset by sectarian squabbles and high moral dudgeon, and the land was frequently assaulted by encroachments, road-building and park construction as well as the natural hazards of fire, wind and landslides. Exhumation is nothing new, since overcrowding often resulted in the accidental unearthing of unmarked remains when new graves were being dug. It was alleged that some of these were quietly and unceremoniously dumped, and in one disturbing instance a child’s coffin lay in the adjacent stream for years. On many occasions the Inspector of Nuisances was called in to investigate “putrefactive fermentation”, “human corruption” and “foul miasmata”, and the sextons often had to battle vandalism, rubbish dumping from opportunistic neighbours and the nocturnal occurrence of what were decorously described as “improprieties”. Some of those activities may still be popular, if the infamous Wellingtonista “Spot the Dog” post is anything to go by, and perhaps the incongruous amphitheatre that overlooks the mass grave sometimes attracts an audience keen on improvised erotic theatre. Today, the only action is a pair of conservatively-dressed men practicing Tai Chi moves, their graceful movements tracing slow arcs above the restless resting place of thousands.

Near the memorial , there’s a grand old tree festooned with epiphytic ferns and mosses. I once took this as a wry symbol of post-colonialism: the English oak succumbing to native ecosystems; the invader reclaimed by indigineity. Now I find that the tree has a name and a history. It is the “Selwyn Oak”, supposedly planted by the eponymous Bishop, and even though he returned to the old country, his association with the founding of the cemetery warrants some recognition here. He had a reputation for religious tolerance and fair dealings with Maori, but there is a darker note in his reaction to the drift away from “pure” Anglicanism towards the syncretism of Hauhau: “watching over the remnant of a decaying people and the remnant of a decaying faith”. In that context, one might indeed read a defiant response in the sight of lush native climbers engulfing the rigid Anglican limbs of the good Bishop’s oak — though in that case, I’d rather not think about the ominous creep of Tradescantia around its roots.

“It is a waste of time to deny the past. It is there, behind us and in us.” That’s what Alington wrote in her epilogue to Unquiet Earth, and it’s thoughts like that that keep me looking for connections. Even overinterpretation can be fertile, an imaginative tangle of roots and branches that treats the past not as dry factual bones but as living seeds still capable of engendering new stories. But I’m stumped by the shiny black cube that marks Herbert J Williams’ grave at the base of the tree: it bears Masonic insignia, but I can only link it to the use of black cubes to secretly veto an unlucky applicant. Has Williams been posthumously blackballed, barred from the Craft in the afterlife?

I’m on safer ground with the more explicit signs that litter this stretch of compensatory parkland: plaques that celebrate and commemorate, though sometimes in rather tokenistic ways. The installation of a plaque “dedicated to the memory of persons who have contributed towards the betterment of the New Zealand environment” in a place that has been so thoroughly desecrated is so far beyond irony that I can do little more than leave the thought to fester by itself. On the other hand, as motorway environs go, this landscape has been remarkably well-handled. The combination of Brutalist energy and the English picturesque tradition (footpaths meandering lazily through bosky glades, while a slender raw concrete footbridge soars and curls overhead) could have seemed jarring, but it goes far beyond the usual “mitigation” planting, and despite its conceptual contradictions it seems to have settled into something resembling charm.

We have Helmut Einhorn to thank for that. A fierce opponent of the motorway project, he was initially shunted out of the Ministry of Works to a harmless secondment, then assigned what must have been a bitter task: “coordinating the architectural and aesthetic considerations” of his hated road. Would it have been more principled to refuse complicity with a brief that he believed to be fundamentally damaging and wrong-headed? Or would that have been futile, compared to the opportunity to influence the outcome for the better, even in what he thought must have been a superficial way? Some of his efforts failed: a proposed piazza across the motorway, complete with exhibition buildings and relocated headstones, was quietly downgraded to a narrow pedestrian bridge, though the reinforcing for its supports still lie hidden between the lanes of the highway. But the combination of thoughtful planting, subtle textures and occasionally dramatic engineering brings a touch of émigré flair to even some of the grimmest stretches of the motorway’s path. I appreciate the crisply geometrical dynamism of the stanchions as I walk through the otherwise sub-Milton Keynes carpark between Bowen St and Ballantrae Place, avert my eyes from a violently pastel collision of Tuscan villas and Sydney terraces, then sweat my way up the narrow steps to Hill St.

From the overbridge, I get the merest glimpse of what should be the most nationally significant building of the journey: the Beehive. If you’re looking for Masonic symbolism, then it’s hard to go past beehives, which are among the emblems presented to a Master Mason. They represent the apian virtues of duty, industry and cooperation — which should produce predictable sniggers, particularly among those who find it far easier to satirise all politicians as venal, indolent and bickering than to actually engage with political thought. At least one conspiracy theorist has gone beyond pointing out the Masonic connection to suggesting a resemblance to the Tower of Babel, though that author’s pathological pareidolia also extends to finding all-seeing eyes throughout Civic Square and child-sacrificing Illuminati in Capital E. I rethink my attitude to imaginative overinterpretation.

Sir Basil Spence — who may have sketched his Beehive design on a napkin, though his earlier, more detailed drawings show that it was far more thoroughly thought-through than the anecdote suggests — was probably not a Freemason, but the commissioning PM Keith Holyoake certainly was. Of course, not all that long ago it would have been odd if a Prime Minister or Governor General were not a member: all of the excitable occultist paranoia and New World Order wingnuttery obscures the fact that the Craft is at heart little more than an old-boys’ club for well-connected white men. There’s far more psychogeographical significance in the architectural moves that Spence actually intended (a round building as a “peg” to anchor the curve of Bowen St; turbine imagery as a late manifestation of Modernism’s celebration of heavy industry), and more political significance in the very real constitutional cluster of Parliament, judiciary and Treasury, than in the most ingenious crypto-Masonic fantasies.

Beyond Hill St, the motorway takes a slow curve to the right, shifting alignment from the foothills route to the old Thorndon gully, falling in line with the long straight slash of the Wellington Fault. I flow into the transition, ready for the next stage.

This is the Dan Brown leg of the journey.

And the Map of Notional Significance has been updated.

Thanks for all the work, Robyn. Just one little correction: there’s some rogue HTML in the link, but this should work.

Robyn’s link has been fixed. Sincerely, The Wellingtonista Magical Elves Brigade.

Thank you, Head Elf!

On the other side of the motorway is the Ramp Path, a path made out of land set aside as a motorway offramp (or onramp?) that was never realised due to budget cuts. It’s worked out nicely, with a pleasant meandering path making its way along what would have otherwise been a concrete trough.

There’s something about the landscaping around this part of the Wellington motorway that really works. Even though it’s not particularly fun walking past a giant motorway, it is at least tolerable in many places. It’s sad that the Bypass didn’t manage to have a similar relationship with its environment. Unless you count those “pocket parks” aka “Oh shit – what are we going to do with this triangle of land between these two busy roads? Hey, let’s stick a park bench in and call it a pocket park!”