Notional Significance: Flat

[See all Notional Significance posts]

I set off along Taylor Terrace, and into the slow, steady heart of the suburbs. So far my path has traversed urban, edgelands and rural landscapes, with occasional tangential encounters across suburbia’s ragged edges. But here I am engulfed, flanked on both sides, striding out its loose domestic rhythms: hip, hip, gable, hip. The motorway is just a quarter-acre’s depth from my right foot, but its drone is nearly drowned by the harsher buzz of mowers and late-summer cicadas, its pungent monoxide lost among the grass clippings. The sudden limbic snap back to schoolground memories.

The road rises and falls like a deep ocean swell, occasional breaks in the hedges revealing the flat valley to my left. Flatness is so much its defining feature that until the 1950s it was officially known as “Tawa Flat”. It’s the homely flatness of an egalitarian ideal, a fading dream in a post-Rogernomics country, but still legible in the modesty of these homes—scaled to human limbs and aspirations, unlike the bulked-up Hardie’s castles on the other side of the highway. The hard-won flat line of a life without surprises, when families struggled towards comfort rather than polystyrene columns. Not that dreams are absent: they just tend towards the harmlessly whimsical (an angler’s idyll airbrushed onto the side of a caravan; a garage door wallpapered in imitation brick; a clapped-out Caprice restored to a loving sheen on the roadside verge). It’s the flatness of Lynn of Tawa’s vowels, a caricature (none-too-lovingly scratched with fake nails on a worn-out blackboard) of lower-middle class middle New Zealand. And so Tawa became a metonym for post-war suburbia—simultaneously a cruel classist joke and a Boomer origin myth—and staked a claim to national significance of Pavlovan eminence.

The mouth of the cul-de-sac eventually disgorges me at a roundabout, and I turn up Tawa Terrace, following the highway as closely as I can. A wooded eminence rises above the flatness: one half of a hill that was bisected by the motorway. I drift into Court Road, and the route turns wild once again, bending across a former watercourse and up the hillside. A strange, aloof house, its roofscape a collision of acute angles, sits sentinel upon the peak. The road twists and narrows, peters out into a track. The crunch of gravel. The snap of broom and the crushed licorice scent of fennel. The sun’s insistent pressure on my chest, resisting my passage.

I concede a pause. From here, I can look out across most of Tawa. What the 1897 Cyclopedia described as “a picturesque arcadian settlement” is now a softly rumpled quilt of roofs and greenery, fraying at the edges is it folds into the forests beyond. Its centre, if indeed it can be said to have a centre (the big-box bandits having exerted their centrifugal forces), is marked by a supermarket, the world’s most timid attempt at a Brutalist office block, and of course churches. It’s a Wellington truism that Tawa has more churches than any other suburb, but I’ve yet to see any statistical proof, and census data suggests that the populace is no more devout than in other outer suburbs. What it does have is some striking white modernist steeples, including the intricate geometric lattice of Our Lady of Fatima. Tawa’s geometry, sacred and profane: spires, obelisks, roundabouts, culs-de-sac.

Court Road becomes a road again, then at the next junction I turn right and follow Cecil Road as it grazes the motorway before depositing me at the vast green flatness of Tawa College. There are signs: prohibitions on smoking, golf and dogs (and presumably any combination thereof), and the school’s heraldic commandment to “Do Justly”. This mild Biblical encouragement might not have rubbed off on all of the community, or at least not upon whoever’s jagged hand scratched FUCK YOU across the coat of arms.

I trudge across the browning lawns, and thread my way between deserted classrooms to find a tunnel. Inside, it’s dingy but blissfully cool, and I linger despite the rancid air. Traces of graffiti, and graffiti’s erasure, grey on grey. Dead leaves and crushed cans. The ceiling rumbling like an inverted earthquake. The weight of national significance above my head. White light glaring from the far side.

When I emerge, it is onto yet another flat off-green terrace: the other half of Tawa College’s grounds, severed by the motorway’s razor slice. The carriageway’s so close I can taste it. Cars hammer along this unimpeded straight, shimmering in the asphalt haze. I have to weave through the streets of Greenacres (Tawa’s forgotten country cousin), taking Allen and Mahoe Streets until I hit Mahoe Park, and from here I can edge my way along a narrow strip between houses and hard shoulder.

From a hillock I can look north towards the proposed Transmission Gully turnoff. I briefly considered following the proposed Road of National Significance from here, but my appetite for trespass is not what it was. I struggle to even imagine the presence of a new road here…no, that’s not quite correct. I can visualise presence; it’s absence that defeats me: the vanished trees, the sliced-off hillsides. And NZTA’s plans are a shifting, slithering tangle of absences, quantum voids of negative potentiality that twist their virtual nothingness through solid rock as engineers recalculate their capacity for erasure.

In the tangible world, I scramble down a slope and emerge beside the Collins Ave underpass. Back to the rural edge. I can’t help smiling at the juxtaposition of the street name opposite me—Little Collins Street—with the spray-painted sign beneath it: “HORSE POO!”. This is as far as one can get from the world of Melbourne boutiques.

I pass through the underpass, with its quaintly cobbled banks, and instead of turning immediately right and following the highway through Arthur Carman Park (“Carman” seems an apt name for these neighbourhoods), I detour a couple of blocks to the Linden shops. This is largely a survival mechanism—I haven’t eaten or had a cold drink since Johnsonville, which seems an age ago—but Linden holds its own charms and stories. Dairies either side of the level crossing, at least one good fish and chips shop, and a shop specialising in South African meats. An exemplar of 1970s late Modernist suburban retail architecture: rakishly angled shop windows divided by walls of bright geometric tiles and imitation pebble.

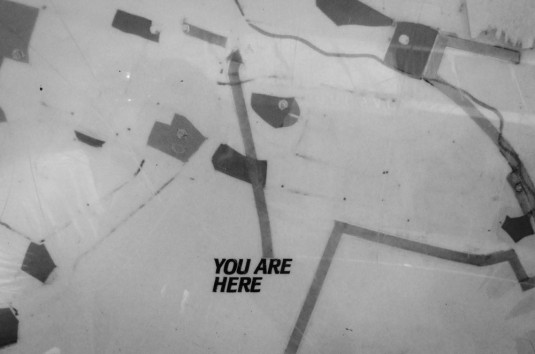

But it’s all suffused with a deep sense of absence, of thwarted ambition, of suburban aspirations left to gather dust as the highway rolls past into a future that has no need for them. The signs are there—“Regal Manufacturers”, “Divine Wedding & Bridal”—cracked windows into empty spaces. A sign reassures me “YOU ARE/HERE”, but the map has faded into an accidental Malevich: an abstract composition of ochre lines, green polygons, and a blue squiggle that wanders aimlessly across the forgetful grey field. A suburb that once dreamed of being Regal and Divine (Lynn of Tawa in a tiara from Farmers?) now knows firmly that it is here, but “here” has lost all shape and context.

Thank you, I no longer know tawa, but just briefly i was there again

thank you.

Great post, Alf, enjoying your comeback. Incidentally I walked part of the proposed transmission gully route earlier this year, and wrote about it here, with reference to your very fine work: http://risingtogale.com/2014/03/17/transmission/

Beautifully written, as always. Curiously, I was there in the same location the other day, traversing possible routes of the RoNS, and stopped in to the Linden Hall to see the NZTA (actually Opus, as NZTA are too scared to show their heads) roadshow into the Takapu Valley “consultation”.

Arthur Carman (1902 – 1982) was a top bloke apparently. He wrote some excellent books, mainly local history + rugby & cricket histories (including the definitive history of Tawa, “Tawa Flat and the old Porirua Road, 1840-1970”). Always nice to see a park named after a writer.