Notional Significance: Up and Under

[See all Notional Significance posts]

The path sidles away from the road. To my left, and indeed to almost everyone’s left, is Wellington’s radical headquarters, 128 Abel Smith St. It’s well over three years since the shattering dawn when police smashed down the door, seeking evidence of so-called “terror camps”, but the Urewera 18 are still to face trial. It’s the sign of an astonishingly arrogant disdain for natural justice that they may never be tried by a jury. But 128 remains, and remains defiant. Signs of constant and multifarious struggles still cover the highway-facing elevation of the house, from the faint and faintly patronising appeal to bypass labourers (“Grow kumara, catch fish, but don’t pull down our homes”) to the bloody splatter of the current obsession (“March to end factory farming”).

Further on, the bypassed villas are clean and empty, and mitigation creepers are beginning to soften the noise barriers. It strains the imagination to remember the old Oak Park Avenue: a tight and shambling lane, the backs of stables and small factories, lovingly neglected spaces where people made art, music and ginger beer. Odessa named a song after the place, and sung of the loss: “Everywhere eviction signs/They’re pulling down this part of town and calling it progress/But that’s a word rich people use”. I was never more than an addendum to Te Aro bohemia at the time, and as I struggle to reconjure the brick and ivy − “infested with the memories/faded hopes” − I wonder whether my own memories are at least partly second hand. “Forget the life you never knew”.

Oak Park Avenue (far from an avenue, and with only desultory attempts at oaks and parks) reaches Vivian St. Only it’s no longer Vivian St, but Buller St, ever since someone decided that a street that is now contiguous for pedestrians but not cars could not possibly be a single street. The taxi drivers were getting confused, poor darlings. But it beats me how renaming this short stretch after a street that already exists, so that we have a T-junction of three streets with the same name, could be any less confusing. Names divide and names join.

Not that “Vivian St” has any claim to a timeless connection with the land. On nineteenth-century maps this was still Ingestre St, and where it now leads up the steepening slope to The Terrace, it once joined Whitcombe St, as the southern end of The Terrace was then known. Names slide and names fade.

Up above that intersection (Ingestre/Whitcombe, then Vivian/The Terrace, now Buller/The Terrace), the dark exotic trees beside Te Aro school have long exerted a strange power on my imagination. Their silent looming seemed to want to mark something more significant than playgrounds and a shortcut for students, and my subconscious cast it as a waiting place, a gateway; a momentary catch in the headlong fall from quiet hills into the riotous town. For a while I was vaguely aware that it was the site of the Terrace Gaol, but it wasn’t until I saw Ann Shelton’s photo billboard “Capital” (recently at Bartley + Company gallery in Ghuznee St) that I found out that this was once an execution ground.

A contemporary account stated primly that “the little plot in front of the gaol contains but seven mounds, of which all are neatly preserved and labelled with the initials only of those whose remains lie beneath”. Were the bodies disinterred before the site switched its attention from the end of life to the beginning? Were these conifers witnesses to the gallows? It would be easy to believe that I had subconsciously picked up a grim aura, the psychic trauma of the earth, but rationality suggests that a combination of topographical eminence (along with the Mt Cook Gaol, it would have cast a commanding glare across Te Aro Flat) and the European ambience of a path winding through pine and oak would have been enough to trigger my Anglocentric imagination. If there’s any connection to be remarked upon, it would be the symmetry of the Buller/Vivian/Pirie St alignment: central Wellington’s longest east/west street, terminating each distant vista with a steep rise into dark green secrets.

Rather than detouring up the slope, I carry on along Buller St. That’s the other Buller St (do keep up). There’s something unheimlich about a one-sided street, which makes sense if one follows Georges Perec’s definition of a street as “a space bordered, generally along its two longest sides, by houses; the street is what separates houses from each other”. Without the opposing houses, the space is not bordered, and it cannot hold: space sloshes out from the carriageway; pours across parallel parking, ornamental flax, angle parking; spills over the noise wall and down into the deep moat of the bypass. A few stray splashes dribble weakly against the oblivious backs of Willis St office and hostels, but the power of the space has leaked away, drained into the heedless trench of the motorway. Without borders, there is no space; without space, there is no street.

The dislocations continue at Ghuznee St. Robert Jesson’s Starfish, once appropriately located on Featherston St above former seabed, have washed up far inland on the dry fringes of Te Aro Flat. Spiked up, trussed up, glossed up, they are reduced to trophies, art rudely taxidermied and nailed to the wall to prove a hunter’s prowess.

The street itself is half in limbo. A redundant offramp, that might otherwise have become a park or a building and returned to the city’s grid, is now a kind of gypsy camp for roading contractors. Skips and scissor-lifts, portacoms and portaloos, slumber behind chainlink fences awaiting their nocturnal, subterranean purpose. Each night the camp awakens into an orange scurry of hi-vis vests, road cones and flashing lights, machines and men hurrying into the Terrace Tunnel to complete the long emergency safety upgrades In Time For The Rugby World Cup.

These works have thwarted my plan of following the highway right up to the tunnel portal and then up the green hill as close to the tunnel alignment as possible. I never (well, perhaps only briefly) contemplated an illegal dash through the tunnel itself: only lunatics and those in charge of small children would attempt such a thing. But the NZTA barriers now force a detour, right back to Willis St, and then up a lazily curving path beside a sullen brown fence. This is student country, orientation season, and the shards from their alcoholic rites of passage litter the gutter in oddly orderly rows.

Up on MacDonald Crescent there’s a house once associated with someone who could have taught them a thing or two about boozing. Number 26 was the house that James K Baxter called Firetrap Castle (“Where the rats run free and the grots are smashed/And the leaves grow thick at the window”) when for a few weeks between Jerusalem sojourns he set up a small commune here. He and his tribe “cooked on the fireplace and wrote slogans on the walls”, and it was one of the saltier inscriptions that helped the muckraking Truth reporters bring an end to the squat’s brief life. Baxter’s fierce rejoinder “Ballad of Firetrap Castle” sardonically thanks the press, bureaucrats and police for “completing [his] Marxist education”, and one section ends with “Roll on the Revolution!”

A year later Baxter had succumbed to heart disease, years of alcohol abuse and self-imposed poverty. It was the road that kept rolling on, and the tunnel ripped through the hillside on the other side of the Crescent six years after that. Though divided into flats, number 26 now looks respectable, imposing and almost stately, set high above yet another one-sided road. From here you can almost make out 128 Abel Smith St, still working on that revolution, still fighting the fuzz and the men from the Ministry.

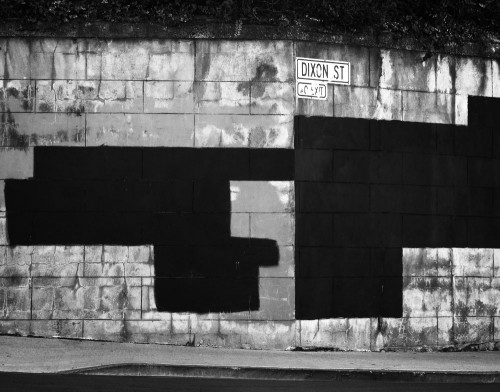

Up on the Terrace, the mix of smart villas and student dives is familiar, though the visible student population looks remarkably fresh-faced and wide-eyed − babyboomer parents helping them shift furniture from stationwagons into hostel rooms − and there’s no sign of Baxter’s dropouts, 128’s anarcho-syndicalists or even the hungover first-years who presumably left the trail of bottles up the hillside. They’re presumably hiding from this shimmering late summer sunshine, a sensible option which I’m beginning to wish I’d followed. Even the graffiti is smiling, with the insides of garages decorated with grinning birds and sunny faces, while the rectilinear methods of the anti-graffiti squads have left bold Suprematist compositions on the blockwork walls.

I turn along Mount St, now a peculiar pedestrianised stump of a street, but once the main path into Kelburn before Salamanca Rd slithered through. The motorway is directly beneath my feet. A little further on, just about opposite McKenzie Tce (once informally known as “Graveyard Lane” since it skirts the Mount Street Cemetery, a reminder of when the locals still clung to the blunt Anglo-Saxon heft of “graveyard” over the refined classicism of “cemetery”) there’s a white signpost that heralds steps down into the bush. Though the post has lost its sign, I remember that this leads through a network of paths to the top of the northern portal.

The bush is scrappy, and overrun by a noxious weed that, if one tries hard enough, can take on multifarious significance. Tradescantia fluminensis is its Latin name, though it was long known by the revealingly hateful name Wandering Jew, and is now more sensitively referred to as Wandering Willy, though even that makes it sound like a nickname for Bill Clinton. But it’s the Latin name that gets the likes of Iain Sinclair excited, due to its connection to John Tradescant the Elder, with his cabinet of curiosities, purloined Ark and links to mystical trickster Elias Ashmole. Tradescantia achieves its smothering invasiveness through its ability to set down roots wherever its stems, even when broken off from their source and carried by humans across the land, touch the ground. But the psychogeography of the Tradescants belongs in Lambeth, not Kelburn. Its story does not belong in these hills, though that in itself could be read as a botanical metaphor for colonial invasion.

One other property of Tradescantia, also mentioned by Sinclair in Lights Out for The Territory, evokes an equally tenuous but nevertheless intriguing connection. A related species of spiderwort shows microscopic mutations when exposed to even minute levels of radiation, and has been planted near nuclear power plants by activists to reveal leaks that would otherwise be denied. Across the road, the neo-Gothic Hunter Building housed the university’s physics department back in the 1960s, and it appears that the good old Kiwi Number 8 wire approach also applied to radiation safety. The results were creeping contamination, bumbling clean-up attempts, a dead physicist and a half-hearted cover-up. The story was buried until the ’80s, and the contaminated materials buried more literally at the Wilton tip, though not after spending some time half-forgotten in attics and garages. I wonder whether the creeping green mat of Tradescantia hides its own subtle mutations, a secret history coiled within its very DNA?

I’m not here to search for mutant weeds, but a waterfall, the only above-ground manifestation of the otherwise long-buried Kumutoto Stream. I’d found it once before, but my mental map is out of alignment, and my attempts to head directly towards it keep leading me into dead ends choked with rubbish and brambles. I listen for the sound of falling water, but all I hear is traffic and the deafening chorus of cicadas. I have to stray further from the trace of the subterranean highway, all the way to the squash club car park, but eventually I find a steep set of stairs and follow them down, through a richer, older stand of forest and towards the vestigial stream. It’s a sad and lonely orphan, trickling past corrugated iron and over a slab of concrete into a shallow pool choked with garden offcuts, then through a few metres of slimy banks and into a battered culvert. Rust, cobwebs, webforge, creepers. But it’s a stream, a real, live watercourse open to the sky, and it’s the only one left this close to the city.

Then I’m out into the sun, blazing and glaring after my stumbles through the shady bush, and on the edge of a clipped artificial meadow. Its topography is awkward, no longer a natural valley yet not quite flat enough to invite habitation, and it’s hemmed in by dense vegetation on one side and the backs of houses on the other. I feel for the thrum of traffic beneath the turf, but nothing comes. A discarded white plastic sheet lies like a shroud upon the grassy slope, but otherwise there’s just the green land and the blue sky, with towers in the middle distance leading the way forward. I follow their lead and walk north, towards the highway’s rebirth.

“…only lunatics and those in charge of small children would attempt such a thing.”

Indeed.

Now I feel a need to track down Kumutoto. (Incidentally, did anyone realise that Mojo Kumutoto has changed its name to Mojo Waterfront?)

Also, I’m following along on Google Maps. Now that the route has diverged from SH1 itself, I’m coming close to wanting to start mapping the route taken.

I saw that Mojo had changed their name: I’m a little disappointed, given the efforts to recall the name of the stream in the precinct. Still, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

As for the Google Maps, I’ve considered adding the links myself, but have decided against it. I’ve approached this more like a serial piece of literary writing than a collection of blog posts, and for that reason (as well as through laziness) I’ve also decided to eschew links.

Perhaps intrigued readers can try a bit of Googling themselves, and in addition to finding the sources that I used, will serendipitously discover more about the subjects than my own links could provide. Similarly, I will describe some of the locations with more-or-less intentional vagueness, so if they are interesting enough to a reader, the process of tracking them down may in itself become a small journey. Reader-generated Google Maps (perhaps along the lines of Barbara Hui’s Litmap of Sebald’s “Rings of Saturn”) will of course be welcome.

+1 on following along in Google Maps.

I followed the previous instalments in Street View, but that doesn’t cover some of these streets.

If you have Google Earth, you can wind the clock back and forward 10 years and fade the latest bit of the urban motorway in and out. Whoomph!

I’ve just made the Map of Notional Significance in Google Maps, which maps every entry of Mr Rune’s journey.

Thanks, not sure if you’ve had feedback on this, but appreciate you making up this map

“all the way to the squash club car park, but eventually I find a steep set of stairs ”

Blocked off at present for construction of tunnel control building.