Review: The Tigers of Wrath

“Our parents do not follow a traditional perspective, growing smaller on approach. Only later will their true scale be apparent.”

“Our parents do not follow a traditional perspective, growing smaller on approach. Only later will their true scale be apparent.”

– Alan Moore, The Birth Caul

Once, so the legend goes, there were a race of beautiful fiery-eyed children who heard the clarion-call of a new and brighter age; and buoyed by the prosperity wrest by their fathers from the hands of evil and intolerance, these children went out into the world, fornicating in the mud and singing in the fields and disappearing into the East to return with spicy-scented skerricks of timeless truth. And then the world, wicked and cracked, whispered through the free-flowing hair and into the ears of these perfect sprites; and they learned too many words, and their world became ruled by black mathematics, and they built towers of glass and stone into which to throw the gold and baubles that were now their unreason for living (if you could call it that). And as their prophets grew older and dumber, they shook their heads and told their own children, we have failed, and now you must live in the ruins and scaffolding of our abandoned dream. And, long story short, that’s how we got Smells like Teen Spirit.

Tigers of Wrath is a retelling of a generation’s sustaining myth: the story of how Baby-Boomers are the worst. The story has been told before and will be told again; the names have been changed to protect the guilty even as they sit in the audience, beating their chests and intoning mea culpas like a Hail Mary. Yes, if there’s one group who love to watch Boomers fail, it’s their kids; but if there’s another, it’s the Love Generation themselves, who just can’t get enough of being told how glorious were those days of unshaven, chest-beating earnestness, and how dark the silence when it came time to stop the record.

Playwright Dean Parker confesses he never went on a “China trip,” but apparently the phenomenon was in the early ’70s a near-ubiquity among New Zealand’s cloves-‘n’-sideburns set. Parker’s play begins at a rest-stop on one such trip, during which lives’ courses are set, love is won and lost, and Maoist flavour-text gets quoted a couple times. You can almost (mercifully, almost) smell the nag champa and disdain for Western standards of hygiene. The show’s three-hand principal cast evoke a rich wandering pathos, sketching a New Zealand a thousand miles away and a China whose insurmountable alienness can be processed only by revolutionary rote and tokenist admiration.

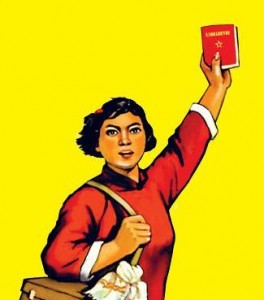

It’s an East/West dichotomy more concerned with the florid sheen of Mao’s Little Red Book than with parsing its contents, Parker building characters whose politics are driven primarily by their hearts and hormones. For the second act, wigs are shed and makeup darkened for a twenty-year flash-forward to the New Zealand of the 1990s, and it’s this masterful centerpiece that’s the play’s strongest: all pithy politicking and estranged egos, a Fall whose cause will become teased out over the show’s remaining length. Ripped from the yellowing headlines of Evening Post front pages, Kate Prior’s Trish becomes handmaiden to the infamous Lesbian Conspiracy that ousted Mike Moore from his short-lived Prime Ministership. A knack for the enduring mythology of Beehive politics will serve audiences well here, as Prior’s wide-eyed revolution-tourist (she can’t understand why a traveling Maoist can’t visit the Great Wall) morphs into a guffawing, eye-rolling Thorndon insider. Prior’s performance is the play’s best, even through a narrative that disappointingly cheats her character out of a seemingly-crucial third-act catharsis.

We’re left with less than initially promised: the inquiry that Parker claims as his inspiration scarcely sustains its own act, let alone the homebound confrontations that follow. A seemingly utilitarian subplot drives another character’s undoing, handled with far less curiosity or sympathy than the adventure which began the show; the Classic Hits of Middle New Zealand are afforded a narrative prominence they can’t sustain, particularly after decades’ worth of service as IRD hold-music.

But maybe this too is true for the Boomers – and if they’re singing yesterday’s anthems at lonely-hearts karaoke nights like that of the play’s final scene, you can bet that one day, they’ll be singing Come as you Are.

The Tigers of Wrath by Dean Parker, directed by Jane Waddell, on at Circa Two until 1 Dec