As I approach the tunnel mouth, I can’t help but notice the looming cliff to my right. I try to imagine the promised/threatened second tunnel, and the impact that its eastern portal will have on the landscape. I envision a giant tunnel-boring mole bursting from the mountainside, like one of Dune’s Sandworms, or the rogue tunneling machine that terrorises New York in Jonathan Lethem’s Chronic City.

The tunnel itself seems invitingly cool at first, but the sensation doesn’t last. Soon it’s a roaring, honking, stinking hell, lit a sickly, sulphurous yellow. The acoustic and bronchial revulsion is intense enough for any pedestrian with the gall to invade this vehicular underworld, but I can’t rush: I need to linger, to record sensations, to gauge and engage with the tunnel as a place, not just a route. Someone has scrawled “Welcome to the gas chamber” at the entrance. Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’entrate.

If this is the lair of a devil, it’s surely a horned one. The origins of the “beeping game” are disputed: some claim that it originated as a tribute to Phillis Symons, while others suggest that in its early years the tunnel’s primary traffic was on foot, so the few drivers used their horns to warn pedestrians. Now it perpetuates itself, an empty symbol, a ritual carried on purely for its own sake. It’s the degree zero of communication, language reduced to plaintive one-note signals, reaching out from one hurtling metal cage to another, reminding each other that human beings are inside.

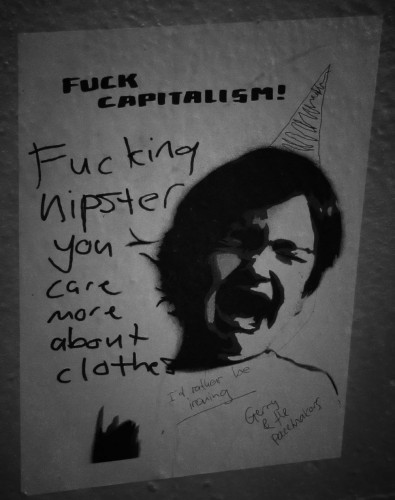

Other humans have taken the time to register more nuanced messages on the walls and floor of the pedestrians’ narrow refuge. There are Pacman ghosts, watchful and mute; rough-stenciled political slogans (“TO BE WHITE AND IGNORE/WHITE PRIVILEGE/IS TO ENSURE THAT/THIS SOCIETY STAYS RACIST”); body outlines invaded by totemic animals. One poster has become the site for a pithy discourse on the gentrification of the anti-capitalist movement — “FUCK CAPITALISM!” leads to “Fucking hipster you care more about clothes” — before spiralling off into irony and solecism. “I’d rather be ironing”, “Gerry & the pacemakers”.

It’s a relief to be out in the real world again, though the trench continues as a deep raw cut, so I’m still some way from anything resembling natural land. The north side is proud of itself — all crisply-engineered concrete and brass plaques — but the south side is a bodge of lazy and leprous shotcrete. Above the cutting runs Paterson St, one more potential victim of the hungry highway. The tunnel, a shortcut born of Depression, cheap labour and a dogged faith in the automobile, is preparing for further expansion. It’s time has returned.

Among the threatened houses is number 7, tucked back behind a nondescript block, but with a “fancy colonial” style and sweeping driveway that attest to its grander history. It was built for Waring Taylor (politician, fraudster, “well-meaning muddler”), and is likely to have been visited by his sister Mary (shopkeeper, pioneer feminist, delicately described as a “close friend” of Charlotte Brontë). For decades it was the “Archbishop’s House”, but more recently it has been infamous as the venue for spectacularly riotous parties. A Paterson St party was something of a rite of passage among certain sectors of young Wellington: my own experiences were necessarily hazy, though I remember the artists, the DJs, the actresses (especially the actresses).

The road swoops again, seemingly deflected by the curving concrete bastions of St Joseph’s. From the air, the plan is a mashup of cross and koru, but at ground level it seems defensive, a shield of blast walls to shelter the congregation from the seething traffic. The concrete is engraved with a pattern that could be waves, scales, or fish, but if they are indeed Jesus fish, then they’re very mixed-up Ichthys: through repetition and Escheresque overlaps, they could be swimming either up or down the highway.

Come to think of it, I can’t tell whether my own journey is upstream or downstream. Is the airport the source of Wellington’s Road of National Significance, or its mouth; the spring, or the estuary where it loses itself in the salty ocean of global travel? It’s an apposite thought as the stream begins to split, separate into northbound and southbound arms as it hits the fissured and contested grid of Te Aro.