Notional Significance: Gully

[See all Notional Significance posts]

The path bends with the motorway, peeling away from the hills, presenting a widescreen panorama of residential Thorndon. I can see what remains of the gullies into which the highway has wedged itself: from the all-but-vanished Honeyman’s Gully (once a duelling ground for lawyers, then filled in for the less fatal contests of Anderson Park), Sydney Street’s dank valley, then settling down beside Tinakori Rd and on through the former Hobson St gully, which until the motorway came through could only be crossed via swing bridge. Behind it all, Te Ahu-mai-rangi (aka Tinakori Hill, aka Mt Wakefield) looms like a vast green wave, now partly denuded in the hope of a native renaissance, but still concealing quarries and tunnels (the lust for gold) in its darkly hidden folds.

Between hill and highway lies a narrow band of houses, many of which are home to the sort of people that inspired the t-shirt slogan “Thorndon: Looking Down on the Rest of Wellington Since 1840”. And though this was once a representative core-sample through a stratified society (grand mansions, proud villas, mean little workers’ shacks), you won’t find much of the proletariat here today. If there are social divisions now, they’re perhaps exemplified by antagonisms between two middle-class gangs: the Thorndon Society vs the Thorndon Residents Association. The former are seen as Old Thorndonites (linen-jacketed heritage architects, classically-educated matrons resplendent in handcrafted broaches), staunch veterans of the Motorway Wars still proud of the concessions they wrung from the Ministry, and with a mixture of self-deprecation and half-jocular hubris they are able to caricature themselves as the “Thorndon Mafia”. The latter might be seen as newcomers, lawyered-up social climbers keen on a Thorndon address but not on the lifestyle limitations of a bijoux cottage, and under the libertarian banner of “private property rights” (the inalienable rights of the alien Right) they’ll rage against anyone who tries to stop them bunging on a double garage, satellite dish and media room.

For those of us who associate Thorndon with this sort of bourgeois smuggery and house-price-obsessed babyboomer tedium, it’s surprising to learn that it wasn’t always associated with social propriety. In fact, it could be a downright riot. Under Sir Julius Vogel, Premier House became so notorious for its bacchic fancy-dress parties that it was nicknamed “The Casino”. Headlines panted about “Gay Goings-on in Goring St”, where jazz-age decadence ruled at a “most exclusive” cabaret. The bohemians got in on the act as well, and it was at that cabaret that Iris Wilkinson (the future Robin Hyde) learned the latest dance moves from the famous Miss Borlase. After their brief affair, Rita Angus and Douglas Lilburn lived as Ascot St neighbours, she in her cottage conjuring menacing cloudscapes above the tin roofs, while he composed for an electronic future in his black and white modernist house. Fleur Adcock (and her new lover) lived with her previous lover Alistair Campbell (and his new wife Meg) in what must have been an emotionally crowded Tinakori Rd house. Today, the Moorings is known as much for booze-saoked arty parties in its stylishly disheveled ballroom as for its history and architecture. Katherine Mansfield could have waited, and Bloomsbury might have come to Thorndon.

But of those goings-on were going-on across the gully, whereas on this side I find myself trailing along the flank of institutional Thorndon: ministries and embassies, schools and churches, memorials and tennis clubs. There are towers on nearby Molesworth St, but here the architecture takes its cues from the motorway — long, low and infrastructural, the Correspondence School is textbook Brutalism, while the Ministry of Health is a PoMo ziggurat in sleek whitewash and smoked glass.

By now, I’m walking parallel to the Wellington Fault, the strongest influence on the intersecting grids of Thorndon. Grant Rd and Tinakori Rd flank the fault zone itself, a hidden battleground of crushed and twisted rock at the base of Te Ahu-mai-rangi’s violent scarp. The other shaper of the street pattern is Thorndon Quay, the former Esplanade that sent parallel ripples inland to define Hobson and Murphy St. In between, though, there’s a vestigial grid formed around the axis of Molesworth St, and no obvious geographical features to drive it. Were the lines of Hill and Hawkestone St drawn to roughly follow the Pipitea and Waipiro streams, and then Molesworth drawn perpendicular to these? Instead, I like to think that Molesworth St was intentionally aligned with the distant peak of Mt Kaukau, and indeed it’s an exact straight line from the government canyon to the communications mast that winks every night in the windswept northern suburbs. It would strike a note of formal alignment that’s usually absent from our city: otherwise, our roads follow faults, scarps and gullies, not lines of power but of weakness, of least resistance.

The path beside the motorway is littered with plaques. One bears a name that can still send shivers through anyone of a certain age: OFFICIALLY OPENED BY RT HON R D MULDOON C.H., PRIME MINISTER. Others are self-congratulatory, crowing of engineering awards (“Outstanding design and care for the surroundings have restored and enhanced the quality of the environment traversed by this new road”). And indeed Einhorn seems to have been having fun here, especially with the variety of supports for the overbridges. I give them names: this is the Herringbone, this the Springboard; these are the Cubist Trousers and this one’s the Flying V.

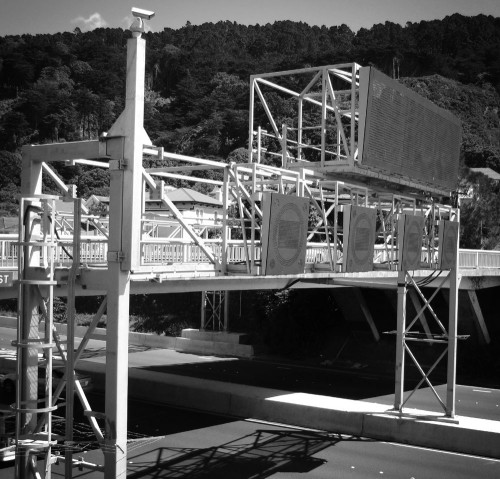

Recent additions lack anything resembling whimsy, or indeed any semblance of grace. New electronic signs are borne on lumbering metal gantries, grotesquely over-engineered and encrusted with cameras and barbed wire. It’s as if a few LEDs carry the entire weight of the motorway system, the bits and bytes of traffic data carved in stone rather than flickers of light and electricity. It carries me back to the billboards at the start of the highway — massive legs bearing flimsy advertising messages — and all the heavy metal infrastructure required to gather, transmit and display incorporeal information. Cellphone towers, repeater stations, stumpy pillars for incongruously dainty cameras. It seems that the symbolic economy is far from weightless.

I wind away from the motorway clamour, seeking a lunch break in the Summit building. It’s a bold wedge, marking the confluence of Molesworth and Murphy streets just short of the motorway — three M’s, one for each of the three Thorndon grids. Its elevations are also grids, their faux-Mondrian colours beginning to fade after only a few years in the sun and wind. Caffeine and cold water do their trick. It’s my first real stop since Ghuznee St, the sun beating down relentlessly on a rare still afternoon, and I’ve many kilometres of highway-chasing still to go today. Across the street, the American embassy is an essay in imperialist paranoia (perhaps not unjustified given attacks on their embassies in more volatile countries), bristling with masts and flagpoles (messages slyly intercepted or proudly flown), cameras and tanktraps, dishes and domes. Even from inside the cafe, I feel nervous about taking photos, almost worried that the guards might charge across the road and grab my camera. Perhaps I should have shaved.

Replenished, I wander on and into more salubrious surroundings. Katherine Mansfield Memorial Park (another Einhorn design) and Katherine Ave recall Thorndon’s favourite daughter (or at least, the favourite daughter of its heritage industry), even if on this side of the highway all traces of her presence are gone. The park wears its 1960s providence well: pergolas, brick seating nooks and gently curving berms all speak of a humanist Modernism, interwoven with the bosky shade of older trees. The Lady McKenzie Garden for the Blind is a refuge from the boisterous playground, though the target demographic for this garden would miss the more arresting park users on this uncharacteristically hot day: a pair of near-naked sunbathers. I put away my camera to avoid any unseemly allegations, and cross Hobson St to the side of the German Embassy.

I had planned to simply follow this last stretch of motorway path to the end of the bluff, then down to Thorndon Quay, but when I’m nearly there I notice a roughly-beaten path that leads up through the scraggly vegetation to my right. I scramble up, ducking under branches, and come across the unavoidable signs of habitation. An improvised hammock; the battered metal frame of an office chair; bottles, bags and the dry ashes of bonfires. The scrub opens up, through trees reduced to bony stumps, revealing a hidden grassy clearing, a lookout wedged between high fences, cliffs and razorwire. From here I can see the wide grey tumble of the railyards, the hills and glassy harbour, and the motorway swooping out on concrete legs, reaching for the distance. It’s a commanding view, but the detritus around me tells me that for the occupants of this invisible eyrie, this is not the sort of “looking down on Wellington” that the t-shirt was talking about.

Err… Douglas Lilburn, not Charles. Though Rita Angus called him ‘Gordon’.

http://sounz.org.nz/contributor/composer/1063

His house (22 Ascot St) is now made available to the New Zealand School of Music Composer-in-Residence.

Of course! Not sure why I thought it was Charles … must have been reading about Charles Brasch or someone. I’ve fixed it now: many thanks

The house is by Frederick Herz Schwarzkopf, and is quite a little gem. Yet another example of Austrian and German emigre architects making their mark along this route: there’s Einhorn of course, and I’ve skirted a couple of Plischkes, and there’ll be more to come.

I give them names: this is the Herringbone, this the Springboard; these are the Cubist Trousers and this one’s the Flying V.

In the orange Wellington Urban Motorway book, the Hobson Street overbridge is described as a “Swedish table leg” structure. I have googled this, and have found nothing that relates to bridge design (or IKEA, for that matter). So I wonder if the designer made up that name – I imagine that Swedish furniture design would have been quite in vogue at the time. It probably sold it to the right committee.

The Map of Notional Significance has been updated.

If one stands on the top of Newlands, Ruskin Rd lines up perfectly with the Wgtn Airport Runway