Notional Significance: Clearing

[See all Notional Significance posts]

The offramp leads me down into what, for want of a better term, I will call the heart of Johnsonville. The local RSA greets me with a Bofors gun and an ad for its eponymous restaurant (“Family Friendly Environment”). Along with the Salvation Army, Super Liquor, a service station and a fast food chain, this forms the southern gateway to the capital of the northern suburbs: a tangled semiotic spaghetti of war, booze and religion; convenience, gluttony and family; topped off with a slick of oil. The Kiwi dream.

The main road is a haphazard strip of chain stores and brave but unremarkable local enterprises. I need one last snack to round off the long day’s walk from Ghuznee St, and I remember the cruel joke: “What’s unique and worthwhile in Johnsonville? Nada.” So I stop at the self-proclaimed “NZ’s greatest bakery” for an admittedly better-than-average savoury roll, before cutting back to the railway station through a mall that seems all the more lost and desultory when seen against glistening future visions of the mall-to-come.

A week later I return to Johnsonville, preparing for the next leg. For the third Sunday in a row, it’s preternaturally hot and still, and in other circumstances, it could be called glorious. The train wriggles and clatters through gorges and cosy inland valleys, Ngaio’s Tarikaka railway settlement recalling the days when the Wellington-Manawatu line was the heroic precursor to the North Island Main Trunk Line. But the carriages now squeal to a rude halt at Johnsonville, the way blocked by a rough-edged concrete cuboid, the former main line still faintly legible in the soft curve of Moorefield Rd.

Further along the street, stranded between the medical centre and an estate agent’s, a memorial lamppost (“Erected by his friends to the memory of the late Tr. L. C. Retter who fell at the battle of Bothasburg, South Africa”) stands out as a rare remnant of the past. Behind it, a concrete balustrade looks like half of a bridge, though it has no companion across the road, just a McDonalds carpark. Once the stream enters the underworld beneath the balustrade, there’s no hint of where it might end up. For Johnsonville straddles a cusp between two catchments, and the waters in this glorified ditch might end up in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, or they might begin the long fall towards Porirua and the Tasman Sea. From a hydrological perspective, perhaps this should be the “natural” northern boundary of Wellington, where the gravitational pull of Port Nicholson finally loses its influence and the lay of the landscape begins to tilt northwards. But the flatness of the Johnsonville basin induces weightlessness and indecision. The streams meander lethargically between lots, popping up in back yards before slithering back into culverts, forgetting their way just as they themselves are forgotten beneath the suburban plat.

But hunger has its own gravity, and I’m drawn on in search of honest stodge in a greasy-spoon caff. I negotiate the Scylla and Charibdis of McDonalds and KFC, pass up on the appetising combination of “Health Shop J’Ville” and “The Roast Canteen” (both conveniently located beneath the Lychgate funeral home), and settle on something called “Fresh Bun”. This seems at first like the closest approach to honesty, but then appears to be a Mr Bun ripoff: a one-off low-rent suburban café, imitating a nationwide chain of low-rent suburban cafés, that are in turn a mass-produced commodification of the traditional Kiwi low-rent suburban café. Baudrillard would be suffering a simulacrum migraine by this stage, as he contemplates the replica Chinese swords and dusty plastic daffodils beneath the acoustic tiles, but I’m undergoing the transition between what Kingsley Amis called the physical and the metaphysical hangovers. I need hearty saturated fats and strong black coffee; what I get is an amorphous puddle of scrambled eggs that competes in pallor with the soggy, barely toaster-kissed white bread, and the sort of impotable battery acid that even the Americans have learned to stop calling “coffee”. I check the news on my phone, and raise an eyebrow at the name of the WiFi network that pops up: “Saint Death”.

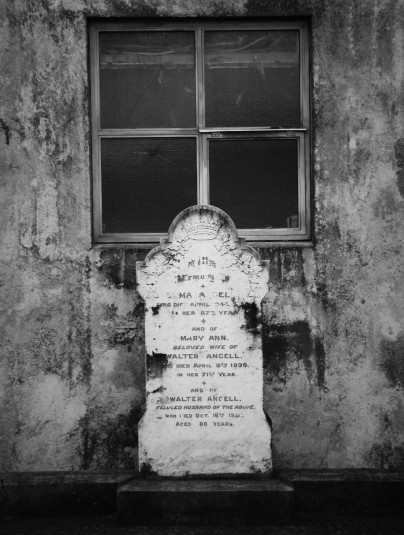

Grease-laden and undercaffeinated, I head briefly southwards then up a narrow service road called Norman Lane. Here, among autoshops, cellphone towers and the back walls of a retail park, Johnsonville buries a bit more of its past. The Methodist Church was demolished in the Seventies, but its cemetery lives on, pressed on all sides by asphalt and steel, stones sinking into concrete or leaned upon by workshop walls.

The lane bends left, sidles between warehouses and the highway barriers, and brings me to the true apex of the motorway. I stand beside the stream of cars and trucks, listening to their Dopplered howl, feeling the pendent moment between ascent and descent, like the halfway mark of a domestic flight when the jets relax and you sense the island slide beneath you. And at this very moment — within reach of the tarmac, surrounded by ribbed armco, stained concrete, no-questions-asked Best Westerns and ripped fishnets of chain-link fencing — I’m treated to the perfect Ballardian spectacle of a ’58 Cadillac, all fetishistic chrome, slithery fins and gaping radiator maw, speeding towards me. A flash of silver and aquamarine, and it’s gone, its turbulent wake plucking at my shirt, and I’m back in the mundane gorse-ridden present.

Will Self praised J.G. Ballard as “the purest psychogeographer of us all, ever dissolving the particular and the historical in the transient and the psychic”, and that’s what strikes me about this transformation of a moment. While Self’s friend Nick Papadimitriou once wryly noted that most psychogeographers “are really only local historians with an attitude problem”, the movement has the potential and perhaps even the responsibility to go beyond that. It’s this realisation that helps me get over my ambivalence towards writers who impose tenuous mystical narratives onto straightforward contemporary landscapes. Like Sinclair’s ley-lines, Sebald’s herrings and Chtcheglov’s “ghosts bearing all the prestige of their legends”, the Cadillac’s gleaming American muscle enacts a totemic alchemy, tangling the imaginary into the fabric of reality, teasing a new significance from the bare factual strands of history and observation.

Ballard and Sinclair would each have their own reading of the underpass that slides beneath the carriageway. The walls are an urban palimpsest of tags and taunts — a desperate collage of names, icons, sexual frustrations (“TREV CAN’T GET IT UP”), greed (“ALL ‘BOUT/MONEY”) and racial defiance (“BLACKPOWER”) — but the laneway then emerges from the underworld into the comfortable suburbia of Arthur Carman St. NZTA’s new control rooms do their best to discreetly settle into the domestic scene, dressed in a modest modernity that’s a tasteful devolution from the spikily honest former complex on the other side of Helston Rd overbridge.

It’s this bridge, with deftly-poised supports evoking the concrete dynamism of a diving board next to a Bond villain’s swimming pool, that reminds me that Johnsonville was once the future. For the stretch of road between here and Porirua was the first motorway in New Zealand, constructed smack bang in the optimistic middle of the Twentieth Century. That was indeed a nationally significant moment: the birth of the motorised dream whereby speed, space and convenience added up to freedom. The northern suburbs bloomed along the motorway’s banks, fed by cheap oil and living on the butterfat of the land, attempting to translate Godzone’s bucolic origin myths into the burgeoning city, one quarter-acre at a time.

And while the Kiwi dream is more than a little American in origin, did this new suburban idyll also have a nationalist significance? We all know Denis Glover’s pithy statements of literary nationalism (“I do not dream of Sussex downs/or quaint old England’s/quaint old towns/I think of what may yet be seen/in Johnsonville or Geraldine”), but was he really anticipating a post-colonial suburban heaven? Did Glover dream of off-ramps, drive-thrus and chain stores? I doubt it, for when he wrote “Home Thoughts” in 1936, Johnsonville was far from an exemplar of metropolitan suburbia, and in fact it was not all that different from Geraldine. It truly was the village that it sometimes claims to be, with stockyards still operating at its centre and cattle driven through the rough streets to the Ngauranga slaughterhouse. Now, Johnsonville is at the other end of the killing chain: it’s the customers who drive to the products of slaughter, circling the drive-in burgeries, the branded feed-lots. Consumer as product.

Between the two Helston Road overbridges, between the obsolescent NZTA installation and the stump of Frank Johnson St, the view is commanding. Somewhere near here was the site of Clifford’s Stockade, one of a string of crude militia stations erected along the Old Porirua Road in the wake of the Wairau Massacre: in the Eurocentric rhetoric of the day, “for the purpose of preventing any predatory incursions of the natives”. This would have been a connection to some of New Zealand’s defining moments, to the campaigns of Te Rangihaeata and Te Rauparaha and the schemes of Governor Grey, but the site has been cleared of all traces. As archaeologists said of the site, “ridge was cut by motorway. Nothing to see.”

Obliteration of history is always part of the motorway deal, but the act of clearing away is a defining characteristic of Johnsonville: before it was even a Ville, it was Johnson’s Clearing. “Clearing” could be read as a verb, and indeed Mr Johnson’s sawmill would have been the beneficiary of much of that clearing, but in its geographical role as a noun it is defined by lack, by what it is not. The salient property of a clearing is the absence of forest, and the practical possibilities that such an emptiness enables. Johnsonville was born from such pragmatism, and today things are still being cleared away and started anew.

Even the one real historic landmark in the town centre, St John’s Church, is the result of repeated obliterations and rebuildings. It is the fifth church on the site: the others succumbed to fire, but the parishioners started over again and again, maintaining continuity of worship on this stubbornly churchworthy eminence. But another erasure has been at work here, one that was willed by the church rather than imposed by misfortune. I’d hoped to find the grave of the Branks family, victims of an apparently arbitrary numerical utu (Henare Maroro vowed to take one pākehā life for each year he had spent in prison; widower John Branks and his three children happened to be the ones to feel his axe), but the front of the church is plain, featureless grass. In the 1960s, mindful of the costs of manually tending a graveyard, the church fathers had it converted to a lawn cemetery. As the Bolton St cemetery had to be sacrificed for speed, the memories of St Johns’ faithful dead were lost in the name of convenient maintenance. Unchosen, unmarked, the Branks family rests unseen, their bodies folded into the forgetful earth, somewhere beneath the respectable, easy-care lawn of the graveless graveyard. Nothing to see.

I’m tempted to write that the presence of death is palpable beneath the wide streets of Johnsonville, but this is where the fantasy of psychogeographical determinism, of the ineradicable genius loci, is so misleadingly seductive. It’s true that the Branks were not the last Johnsonvillians to be hacked to death in their beds, and that the logos of funeral homes compete with fast food outlets for dominion over the streetscape. But given a single visit, geography cannot be disengaged from history, let alone from personal experience and mood. Today is the first Sunday since the 22nd of February. A flag hangs limp. Half mast. A clergyman leads a small congregation in an outdoor memorial service, cool amid the deep shadow of a macrocarpa hedge. National tragedy is layered over personal melancholia, which in turn colours the faded signals of any timeless patterns that I might try to discern amid the shifting landscape.

But if I am to trust my instincts about this place, perhaps what I’m sensing is not the closeness of death. Perhaps it’s just that this far away from the childless liberal bubble of downtown, with its willed or unwilled suspension of generation, the whole honest cycle of life is proudly expressed: get born, go to school, get a job, get married, get a mortgage, breed, retire … and head to your grave watching your offspring begin the same cycle. The metropolitan snob in me wants to say that this suburb offers nothing more than fast food, a slow death, and a quiet forgetting. But while the landscape of erasure (buried streams, cleansed cemeteries, severed railways) encourages this cynical reading, the truth is that Johnsonville is layered not with expunged pasts but with vanished futures. Each of Johnsonville’s pasts was a dream of tomorrow: of a day when the church won’t burn down, when the motorway’s sleek curves brings speed and freedom, when the stultifying cobwebs of the old country are blown away by the international glamour of a bigger, brighter mall.

The same could be said of any outer suburb or any provincial town in New Zealand. If Wellington is supposed to be young, urbane and self-consciously well-educated, then maybe this is where “Wellington” ends and “New Zealand” begins. The sections may no longer be quite a quarter acre, the beer may now come in stubbies rather than half-gallons, and the pavlova comes frozen from Countdown, but paradise can still be found in family, personal space, conformity, security and convenience: all underwritten by the motor vehicle. Along Middleton Road, beyond the roaring gyre of the roundabout, I press on, deep into New Zealand.

Mr Bun a nationwide chain? Give me the address of a Mr Bun outside the Wellington and Hutt Valley area. Just one Bun will do.

Oh dear: I’m sure I remember seeing them in provincial towns as well as throughout the Wellington region. I’ll see what Mr Google can tell me, and edit as required.

Mr Bun – main street Levin

The Map of Notional Significance has been updated. Thank you for your continued adventures, Mr Rune.

And thank you for the mapping: this one was short, but particularly convoluted.

Where has “Gorge” got to? Or am I just a bit dense?

Sorry Pete, I’d dropped the category off the “Gorge” post so it wasn’t showing in the link. Should be fixed now.

Alf – not sure if you can follow this convoluted link – but it takes you to a very strange image of Johnsonville in 1950. Half-completed motorway in the background…

http://find.natlib.govt.nz/primo_library/libweb/action/display.do?ct=display&doc=nlnz_tapuhi1055699&indx=16&mode=Basic&vid=TF&dscnt=0&vl(35124698UI1)=all_items&srt=rank&ct=Next%20Page&frbg=&scp.scps=scope%3A(Timeframes)&indx=11&vl(D31185043UI0)=any&dum=true&dstmp=1308970713973&fn=search&vl(1UI0)=contains&vl(freeText0)=johnsonville&tab=default_tab

Thanks for that link Richard – I can see my house from there!

Ta for the link Richard. Not THAT strange an image really apart from the fact that what appears to be a very pleasant little green village has turned into a banal asphalted strip of suburban mediocrity in the space of 60 years

The branks family are buried in the old St. Paul’s cemetary in Thornton wellington, they were never buried in jville. They are buried with the mum who died shortly before the murders after getting tetanus following an accident.

And the perpetrator of the deed, Henare Maroro, was one of only two people to be publicly executed in Wellington.