Snakes and Shadows: History as Poetry in Chris Tse’s Year of Snakes

Cross Tory Street heading toward Aro; banish the Carrilon’s long shadow behind the white-and-teal Bible Society on your left, Nurse Maude’s mosaic gaze upon your right shoulder. Point your nose toward Tara-Ngaki Street – “shining mountain-peak” – and feel Haining Street incline beneath your feet as Tory’s constant woosh recedes into urban din. The senses strain for a reference worth savouring. In the right wind, L’affare’s rich gold-brown aroma will follow until salty-spicy Vivian Street unfurls on your left; but to the eye, Haining offers little, Media and Image and Print wafting inky acridity.

As the street’s mid-point lulls the tread gently downhill, historic notoriety looms. Round eyes once squinted warily down Haining; behind receded epicanthes were conjured an air thick with opium, grubby gold, illicit sex. Here children were forbidden to play lest a Chinaman shadow them away. Here in September 1905 – the Year of the Snake – goldminer Joe Kum Yung began his long, lonely journey home: his skull ruptured, blood and brain leaking onto Haining, head brought low by the metal slug fired from Lionel Terry’s gun.

“A serpent’s tail will taint / the things we neglect / if we turn from instinct,” Chris Tse has the dying Kum Yung muse: one of the many serpentine references signposting How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes, Tse’s lyric history of Haining Street’s defining crime. Serpents stand for irrepressible reflex, animal cunning buried within soft mammalian mind; and for renewal, the casting of live skin into dead totem. Years of the Snake are times for action: “this is not a year for fence-sitters,” cautions Chinese astrologist Theodora Lau.

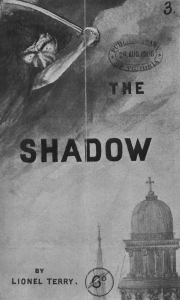

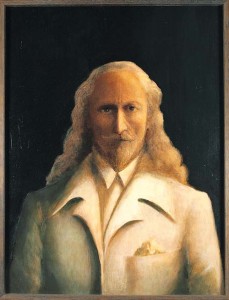

Most of the actions in Kum Yung’s story as it’s told today are those of Lionel Terry. As the gunshot echoed and cordite burned his nostrils, Terry’s feet must have throbbed relief. He’d walked all the way from Doubtless Bay, on a purifying mission from the “Great Gold God” to whom he dedicated the opening pages of his rambling, racist conspiracy-tract, The shadow. The pamphlet, which Terry handed out freely on his pilgrimage, is readable at the Victoria State Library. His self-portrait – Dürer silhouette twisted by a riddling stare – can be viewed at Te Ara.

But the skin Joe Kum Yee shed was sent back East, and we have few totems of the life he tried to make here. Tse plays the role of psychopomp: lending Kum Yee’s spirit voice as it strains against the ropes of history, of circumstance, of tensions scarcely slackened in our time. Joe Kum Yee, who sought fortune beneath foreign mountains, was farewelled by lantern-light, far from Lionel Terry’s asylum cell; but Haining Street sits still in that same shadow.