Review: The Hobbit Companion

It’s not by chance that John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s was the setting that would become the default template for the popular notion of high-fantasy; no arbitrary circumstance that led to Tolkien’s intricately-crafted argot becoming the lingua franca of the sword-and-sorcery genre as it’s commonly understood today. Tolkien, with his fellow Inkling and understudy in Christianity CS Lewis, doubtless would have agreed with the latter that In the Beginning was the Word; but he’d also have responded favourably to the work of the archeo-linguist Owen Barfield, another Inkling, who saw in language a window into the history of human perception itself.

It’s not by chance that John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s was the setting that would become the default template for the popular notion of high-fantasy; no arbitrary circumstance that led to Tolkien’s intricately-crafted argot becoming the lingua franca of the sword-and-sorcery genre as it’s commonly understood today. Tolkien, with his fellow Inkling and understudy in Christianity CS Lewis, doubtless would have agreed with the latter that In the Beginning was the Word; but he’d also have responded favourably to the work of the archeo-linguist Owen Barfield, another Inkling, who saw in language a window into the history of human perception itself.

Tolkien’s Middle-Earth – the setting for the work of artists as diverse as Gary Gygax, Robert Plant and latterly Miramar’s own cineaste laureate, Mr Peter Jackson (aaaand there’s your Wellington link) – is a world predicated by its language. Indeed, while many authors will drag out the umlauts ‘n’ glottal-stops when it’s time for their characters to talk, Tolkien’s entire Middle-Earth oeuvre – Fellowship, Twin Towers, King Kong, the lot – was dreamed up so his lovingly-constructed languages would have some characters to speak them and some things for them to talk about.

In turn, the cottage industry devoted to scholarly analysis of Tolkien’s work may be rivalled only by Dylanology in its obsessive depth of exegesis. Canadian David Day, for his part, has contributed six books to the collective body of human knowledge as to where orcs come from, among them the 1997 Hobbit Companion – here fortuitously rereleased shortly before a movie comes out about same.

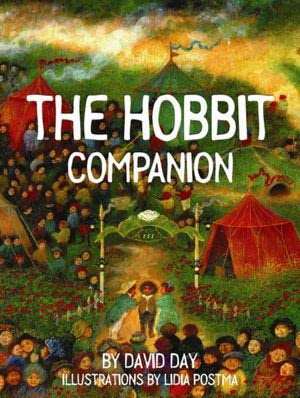

Day’s book has held up well in the ensuing years: a colourful, vibrant coffee-table tome boasting a wealth of illustrations that set the contents apart from the Lee/Howe graphics which, by the time of Jackson’s films, have become all but canonised as the look of Middle-Earth. Lidia Postma’s pencils and watercolors, brightly-colored and satisfyingly messy, carry more than a whiff of the anthropologist’s field sketches, fittingly for this expedition into murky textual territory.

And murky it is. Like Owen Barfield, our author – a published poet – is eager to start unpacking language and waxing homonymous. Barfield’s was the task of tracing English words and grammar back to their source: an up-river journey through the history of language in order to map out the world created in its image. Beginning with the word “Hobbit” itself, Day undertakes a similar excavation of Tolkien’s own etymological inspirations, showing how the author’s stories unfolded through playful linguistic association.

In paying tribute to JRR’s genius, though, Day can get a little carried away: many’s the paragraph that unwinds through a dizzying chain of associations, only for Day to arrive back at the start with a satisfied flourish; readers may wonder more what exactly the point was of going all the way there and back again only to become, like poor class-whipped Samwise Gamgee, a pawn in someone else’s linguistic gamesmanship. Day is right to identify Tolkien not just as an author of prose but as a poet and magical wordsmith; but many of the master’s spells, as recited by this particular apprentice, give rise not to wonder so much as self-reflexive tautological nausea. And these are the 2010s, so we have plenty of that to go around already!

For a “companion” to The Hobbit as a whole, the book also suffers from an uneven interest in its subject matter. Having devoted no shortage of ink to hobbits (general), (tribal history of), (societal organisation of), (dwellings of), (Baggins in; SEE ALSO Took, Brandybuck et al), (Gollum as); we’re more than halfway through before Day even arrives at the novel’s inciting incident. From there, it’s a cursory rush to the end-point, before a premature departure into the post-Hobbit fortunes of the protagonists. It’s a shame Day’s scholarly engagement didn’t stretch to a little more commentary on the journey itself.

Certainly there’s plenty early on which could’ve been trimmed to make space: the discourse on hobbits, which comprises the bulk of the text, is laden with repetition and redundancy. Many’s the erudite paragraph bookended by clunky, inconsistent summarising text which reeks anachronistically of PowerPoint and tends to obscure, rather than crystallise, Day’s point. Would that we might wade through a few less restatements of the similarities between the words “Baggins” and “Bag-Man,” and in turn spend longer at some of the many celebrated waystops left by Tolkien throughout his novel.

Still, the book comes into a hypertext culture of makings-of and behinds-the-scene which scarcely existed on its first publication: by the time the sixth and final Hobbit film (at time of writing) is released, fans will be poring over collective decades of supplementary features detailing every last location, prop and costuming choice that went into Jackson’s Middle-Earth. It’s to be hoped that work like Day’s finds a new audience alongside these, as a reminder that before slo-mo and choral accompaniment were invented, fantasy was once built out of words.